Remember that crazy moment in the Borat movie, when he is at the rodeo and he inadvertently congratulates the crowd for what he calls “America’s war of terror” (instead of “war on terror”). It was fabulous and yet frightening, because the crowd didn’t notice and they kept on cheering.

Something similar has happened with the “war for talent” in that it has inadvertently become the “war on talent”. Is this the product of unscrupulous consultants or is it merely the product of learnt blindness? How could what appeared to be common sense be so dramatically futile? This paper will explain how a simple idea that never defined itself objectively became a goal that was the means of effectively disengaging the majority of workers and managers in organisations.

Talent and the need to have an engaged workforce is a hot topic at the moment. But is talent the right focus?

What is talent?

Ask a group of business people this question and a typical answer is that some people are naturally gifted. Such people come specially endowed to do some amazing things including being the best performers, leaders and team players. The implication of this thinking is that this only applies to the few. This appears to be the mindset of the CIPD [the Chartered Institute for Personnel Development] who state in their factsheet on Talent Management (August 2012) that ‘talent consists of those individuals who can make a difference in organisational performance either through their immediate contribution or, in the longer term by demonstrating the highest levels of potential’. They go onto say that ‘talent management is the systematic attraction, identification, development, engagement, retention and deployment of those individuals who are of particular value to an organisation’. The CIPD are not alone in this approach.

On the surface this appears an absolutely sensible approach as organisations often task HR to attempt to get the right people in the right place at the right time to deliver the business imperatives. Identifying those people with the right ‘talents’ for an organisation would make sense and should lead to success. But how do we identify talent, and what exactly are we talking about? There are many psychometrics tests in the market all purporting to identify various different aspects of each of us including:

- our personality

- competency profiling

- how we think

- our strengths

- our ability to lead

- or ability to make decisions and how fast, and so on

Some of them may even have a predictable element. But can they identify a contextual behaviour like talent?

Some of these tests date back to theories from over 100 years ago, whilst others are based on more recent research from the world of neuroscience. But how useful are they actually in identifying and predicting talented behaviour or capability before the individual has been put into the situation where their talent could or might make a difference? How do these approaches differentiate between ambition and talent or potential capability in future situations? Have they proved effective in identifying talented people to match an organisation’s aspirations at a time when the search for talent is supposed to becoming more difficult?

If we do not really understand what talents are and where they come from, and how to measure their potential, this leads to the question: ‘are we once again heading in the wrong direction?’ We ask this because recently the CIPD produced a press release in which they announced that “the days of sheep-dip leadership and management training are now definitely over”. Once again it has been known for decades (Alliger and Janak, 1989) that the link between learning and changes in attitude and behaviours leading to tangible results is poor. In fact the CIPD suggested in 2007 that such positive correlations were no more than random chance.

If the link between learning and business results is poor what are the implications for pursuing talent if we do not fully understand and agree what talent is? And more interestingly, what are the consequences for those of us who are deemed to be untalented by default of being below what may be an arbitrary line? What impact will such categorisation have on already low, staff engagement? How will managers and staff react to being passed over for a talented member of their team? Are we using a poorly-articulated idea to put in place something that will have devastating consequences on people, business and performance in the future, where the talented become loaded with carrying an increasingly disengaged and apparently untalented majority? We have already seen the devastating impact of low educational expectations in our society, and we have to question whether our businesses can compete with a similar self-administered weakness in a global competitive economy.

Naturally Talented ?

One of the problems with pursuing ‘talent’ is the belief by many that talents are innate, that they have a genetic origin which a few lucky people possess, or that they are possessed by those who ‘survive’ testing. Many dictionaries refer to talent as ‘any natural ability or power’ but such a definition lacks substance and appears to lead to many of us assuming that only a few people have it. This seems to imply that the remainder of us may struggle through life as the victims of our genes which do not quite come up to the mark for the highly-demanding environment in which we live today.

One is reminded of how IQ testing regimes were applied without the results being qualified in terms of the limitations of what the test could actually test. Alfred Binet who first introduced the IQ test, which forms the basis of that used today, did not believe that the psychometric instrument could be used to measure a single, permanent and inborn (genetic) level of intelligence. He stressed the limitation of the test suggesting that intelligence is far too broad a concept to quantify with a single number. How many people over the years have been graded wrongly in our educational system because of the IQ test? What impact has that had for the rest of their lives? Are we going to repeat this mistake with the focus on talent?

Today, we know that in all we do whilst our genes have a part to play, what makes the difference is the focused effort that we can dedicate to get better at something through practice over time. Dr Anders Ericsson suggests that it takes 10,000 hours or 10 years to become an expert using deliberate practice in almost anything and, although the time it takes is disputed by others, the fact remains that people can become good or even great when dedicating themselves to putting in consistent, focused effort. That does not mean we can all become Olympic athletes or concert pianists capable of performing on a world stage but it does mean that we all have innate abilities to become good at something, if or when we choose.

What stops us choosing?

We make sense of not doing something and then explaining to ourselves all the reasons why we did it. We only have to convince ourselves because it’s our choice. What does and will stop us from taking any action is the belief that we do not possess the necessary gene or combination of genes that may manifest themselves as ‘natural’ talents. We all come with the innate ability to do some amazing things unfortunately many of us simply do not try because it does take effort or, as often are the case, social attitudes for conformity and avoiding public recognition are strong. The famous 1920s Hawthorne Experiment noted that factory workers ostracised not only those whose performance was mediocre, but equally those whose performance was outstanding. For example, we are all genetically and therefore anatomically designed to be long distance runners; it was how we survived hostile environment in the past. Yet how many of us use this innate asset? Do we all run to work? We all have the capacity to learn, to be curious and to be imaginative. Unfortunately many of us use our imagination to dream up worst-case scenarios or construct narratives and beliefs that we cannot do things because we are simply not ‘talented’ so we do not try.

The Magic Gene

Finally on genes; there is no magic gene. Science informs us that we do not have a specific gene for specific functions but that a range of genes are switched on in response to environmental factors when we have to do things. It is this combination and the ability to construct new patterns in our brains in response to new challenges that enables us to perform new tasks and with focused practice, demonstrate new ‘talent’. Professor Elizabeth Gould’s work in the field of neurogenesis found that with use the brain produces new neurones and an example of this involving London cabbies’ was reported on in 2006 by Eleanor Maguire and others. Using fMRI scans they showed that humans have an amazing capacity to acquire increased spatial awareness and navigational attributes through practice and experience. They discovered that relevant parts of the cabbies brain had grown enabling them to navigate around the complexity of London’s streets without the aid of a satnav. This reinforces the key message that we can all develop new ‘talents’ or strengths through focused effort.

Fear of Failure – Beliefs

Our beliefs are very powerful. How often, if ever do we test them? At a recent presentation a participant said that she lacked the talent needed to catch a ball. She had tried ball catching and could not do it. She was handed a pen and asked to touch the end of it which she did with ease so her hand-eye capability was fine. The pen was gently thrown towards her and she caught it effortlessly. But when a ball was produced for her to catch she said she couldn’t do it and simply refused to participate. Of course she could catch a ball, but her belief in failure was so deeply embedded in her personal identity that she avoided the challenge. How many of us do this at work when faced with new challenges? Is the real ‘talent’ issue that we need to plan to focus on the supposedly un-talented as well and help them overcome the personal and social conditioning that is the basis of learnt, un-talented behaviours? Is it beliefs rather than talents which impact on what we do and how well we do it?

If we accept that our genes do have a part to play in what and how we do whatever it happens to be, then we need to learn to focus on using our innate assets to improve our capability in different areas. Organisations would benefit from their whole work force growing and developing and not just the ‘talented’; those who appear to tick a box at a particular moment in time or by using a formulaic test whose limitations are never explored or applied to the results. Aviva seem to think so as they applied the simple principle of – the rising tide lifts all boats. Nature sometimes has a way of telling us things.

According to Arvinder S Dhesi (2007) Aviva have an inclusive approach to talent which involves all employees and not just the selected few. He states ‘that the biggest mistake organisations make in talent management is the seemingly relentless focus on the selected few. Most companies believe and act as though talent is a scarce commodity and typically use the term to describe a tiny minority of their workforce’.

According to Arvinder S Dhesi (2007) Aviva have an inclusive approach to talent which involves all employees and not just the selected few. He states ‘that the biggest mistake organisations make in talent management is the seemingly relentless focus on the selected few. Most companies believe and act as though talent is a scarce commodity and typically use the term to describe a tiny minority of their workforce’.

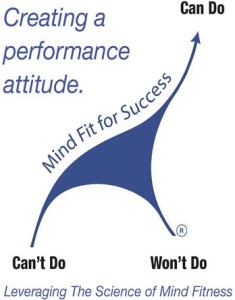

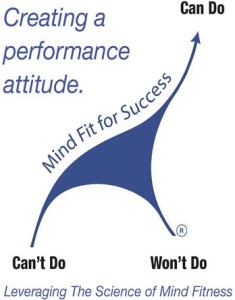

If you want to disengage your workforce simply go down the route of identifying those few people who display the ‘talents’ you are currently looking for or anticipate you will need in the future. The consequences of doing so are immense as disengagement is one of the biggest blockers to business growth. There is only one result as the majority of people will adopt a passive (can’t do) or sometimes active (won’t do) form of disengagement which significantly reduces performance and productivity, turning them into more of a liability than an asset.

No purpose, no passion, no engagement

Find the purpose and you’ll be on the road to success. We are all capable of far more that we believe or imagine, we just have to put the focused effort in. Of course, this leads to the real crux of the matter, ‘Why should I?’ If organisations are locked into ensuring systematic and linear processes relating to people development are in place, where is the passion so why bother? If you are involved in a selected talent based approach beware as it may disengage the majority with a potential outcome of constant battles between the untalented and those special cases.

What will it cost your organisation to play the selected talent game? Can you afford it?

At Mind Fit we focus on understanding the business needs and targets together with the attitudes and behaviours that deliver them. We ensure that the organisation has identified its real purpose, one that once articulated, inspires people to act. If people are valued as people, with the potential to deliver what is needed to grow the business, then they will step up to the mark and perform. It really is that simple. Or that difficult.

www.MindFitltd.com

Written by : Graham Williams & Prof Victor Newman